Opening at Mosaic Theatre Company on Oct. 4, the trilogy’s director, “We know the end at the beginning, so the point of Ballad is to give him that joy back.”

“What if we think about Till’s legacy rather than his death?”

This is the question that animates Mosaic Theatre Company’s The Till Trilogy, an ambitious mounting of playwright Ifa Bayeza’s three-part opus chronicling the life, death, and enduring influence of Emmett Till, the 14-year-old Black boy whose brutal murder in 1955 helped fire the civil rights movement. Two of the plays—The Ballad of Emmett Till, which follows young Emmett on his fateful trip to Mississippi; and Benevolence, a look at two couples, one Black and one White, wrestling with Till’s murder—have previously been onstage. Now Bayeza completes the saga with That Summer in Sumner, a dramatization of the Mississippi trial that set Till’s killers free paired with the story of the Black journalists who endeavored to uncover the truth.

The three plays are staged in repertory with a company of 10 actors; audiences can enjoy the plays in any order, and each stands on its own. The production anchors a sprawling series of free events dedicated to honoring Till’s legacy, with discussions and readings taking place in museums, community centers, and libraries across the D.C. metro area. Together, the unique repertory and extensive programming represent an opportunity for Mosaic, under the new leadership of Artistic Director Reginald L. Douglas, to strengthen local ties and draw audiences into a pivotal moment in American civil rights history—one that Bayeza has described, unabashedly, as the stuff of myth and epic.

Born into a family of artists and activists, Bayeza has always mixed creativity with politics. At 15, she got her first summer job working with her father, a physician, at a migrant camp in New Jersey, where workers often lived in destitute conditions. She vividly recalls one child, maybe 8 years old, whose body was riddled with rat bites and whose face was so world-weary he looked like an old man. “That was a transformative moment,” she tells City Paper. “Seeing what were, to me, the last vestiges of what American slavery was like, I was so stunned that I committed myself to chronicling my people. The wonder and allure of theater was the way I thought I could best do it.”

It was the early 1970s and around that same time Bayeza first learned the story of Emmett Till via a reprint of Jet magazine. Till’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, famously demanded an open-casket funeral so the world could see what Jim Crow injustice had wrought on her child; she urged Jet to publish photos of his body, and the publication quickly took the story national. Like many, the teenage Bayeza was horrified, and changed, by what she saw.

As an adult, Bayeza delved into Till’s life, even meeting with friends and family members who knew him personally. Her findings generated the foundations of The Ballad of Emmett Till, which premiered in 2008 at the Goodman Theatre in Till’s hometown of Chicago. One of Till’s childhood friends spoke to Bayeza personally and gave the play her stamp of approval. “She wrote me a letter to say that she had to close her eyes to realize that wasn’t Emmett on the stage,” Bayeza says.

Since its debut, The Ballad has been produced across the country, even as Bayeza has tinkered with its structure to accommodate different casting demands. Now, with the repertory at Mosaic, she has a chance not only to bring the project full circle with That Summer in Sumner but to mold all three plays into a collective, a process she describes as both exciting and daunting.

She has an experienced hand at the wheel in Talvin Wilks, who directed a previous production of The Ballad and the 2018 world premiere of Benevolence, both at Penumbra Theatre in Saint Paul, Minnesota. Mosaic’s previous artistic director, Ari Roth, attended the debut of Benevolence, and initiated plans to produce the full trilogy in D.C. Wilks remained attached to the Mosaic project despite Roth’s departure in the fall of 2020 and the cancellation of the run originally planned for that year.

While The Ballad and Benevolence are familiar territory, Wilks sees his work as anything but a retread. “Can you learn from and be informed by the first idea, but not necessarily replicate it?” he muses. “This is not like a touring production or a road show; it’s actually, in its own right, a new production.”

These new productions come at a time when Till’s case is garnering fresh press. In August, a Mississippi grand jury declined to indict Carolyn Bryant Donham, the White woman who accused Till of harassing her, prompting her husband, Roy Bryant, and his brother J.W. Milam to kidnap, torture, and lynch the boy. The grand jury’s decision came after the June discovery of an unserved arrest warrant that named all three on suspicion of kidnapping and manslaughter. Later this year, a high-profile film titled Till, directed by Chinonye Chukwu, will bring the events to the screen while drawing focus to Mamie Till-Mobley’s activism.

For Wilks, these developments might make the case seem newly relevant, but it’s all part of a much larger arc. “There’s always been a call on Emmett Till when we’ve traveled through the elements of Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown,” he reminds us. “Emmett and Mamie Till are of our legacy.” As for what the new developments mean for the production, Wilks understands it might bring people to the theater, but insists it doesn’t impact how they think about the work.

What does impact the work is Bayeza’s drive to recapture who Emmett was as a person before he became a tragic icon. During rehearsal for a pivotal scene in The Ballad in which Emmett, known by his nickname “Bo,” pleads with his mother to let him travel to Mississippi, Wilks emphasized the need to embrace Black boy joy. “It’s very important because that’s what Ifa has done with Ballad, especially, and even in the way he travels through That Summer in Sumner,” Wilks says. “It’s giving him his adolescence back, seeing him as a joyful child who loved to tell jokes, loved bubble gum, loved nice things, and was quite a dresser. We know the end at the beginning, so the point of Ballad is to give him that joy back.”

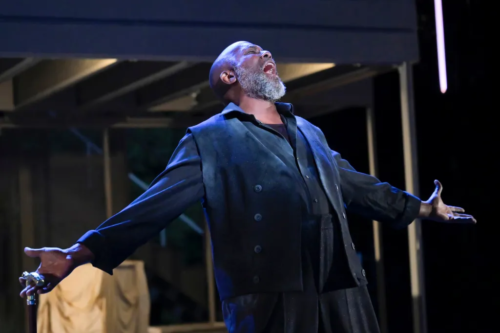

During the scene, Bo is portrayed by three actors, forming his own chorus. The Ballad’s “fulltime” Bo, Antonio Michael Woodard, along with Vaughn Ryan Midder and Jaysen Wright, tease and plead with his mother, played by Billie Krishawn. Wilks and the cast work through the beats at the table in a rehearsal room covered by a comprehensive historical timeline, courtesy of the production’s dramaturg, Dr. Faedra Chatard Carpenter. With the help of choreographer and assistant director Sandra L. Holloway, the scene rises from the table and lands on its feet as a sort of doo-wop number. The three Bos step to and from Krishawn’s Mamie, snapping in time, moving lithe and free like the man he is itching to become.

Throughout the scene, Mamie instructs her son to mind his place—to not even look at White women, let alone speak to them. “Mississippi is not Chicago,” Mamie reminds him sharply. “It’s the South.” The warning rings hollow against his youthful vigor but carries a heavy burden of history for the contemporary audience.

At the Anacostia Community Museum, site of one Mosaic’s many community events, Bayeza performed a reading of the same scene and several others before opening the floor to discussion. Her knowing rendition of Till’s adolescent longings earned appreciative laughs, and the room hummed with agreement as she described the poetry threaded through Till’s history. Others testified to the grim personal significance of Till’s story, echoing Bayeza’s teenage awakening.

Similar events dot the calendar throughout the fall, forming the expansive outreach that Douglas sees as fundamental to his mission. “We want to be an organization that can bring people together, and that’s inherent in our name: Mosaic,” he explains. “Different people, different perspectives, coming together to create something beautiful.” It’s one of many signature projects Douglas is overseeing in his first full season, which also includes a multiyear oral history project focused on H Street NE and a series of infrastructural changes designed to make Mosaic a better place to work.

Like Bayeza, Douglas grew up seeing art and activism in unity with one another. “So much of The Till Trilogy is an opportunity not to forget, but also a call to action,” he says. “A call to not repeat those mistakes of the past, to reconsider our relationship to justice and to one another.” For Bayeza, The Till Trilogy arrives at a point when addressing those mistakes is vital to stemming the tide of White hostility that echoes Mississippi circa 1955. “I’m hoping this will alert us to what we’re up against,” she warns. “And then get us thinking creatively and positively about what we can do, what we need to do, and how we’re gonna do it.”

“Rebuilding the public square is what theater can do,” she adds. As its ambitions attest, Mosaic Theatre Company is running on that same conviction.

The Till Trilogy, written by Ifa Bayeza and directed by Talvin Wilks, runs in repertory Oct. 4 through Nov. 20 at Atlas Performing Arts Center. (The Ballad of Emmett Till opens Oct. 4; That Summer in Sumner opens Oct. 5; and Benevolence opens Oct. 6.) mosaictheatre.org. $50–$64.

Review by Jared Strange for the Washington City Paper.